By Ian Scoones

This is the first in a series of blog posts that bring together PASTRES work from 2018-2023 around a number of themes. In this post, we explore policies and policymaking.

To read through our archive on this theme, click on the link at the end of this post.

Since our research began in 2018, PASTRES work has attempted to lay out a new narrative for pastoralism, challenging many of the misconceptions in current policy.

Our international conference in Addis Ababa in 2023 presented the key elements of the new narrative, and the final chapter of our open access book, Pastoralism, Uncertainty and Development, provides the details. Video commentaries from participants highlight different themes.

This work builds on earlier discussions focused on the Greater Horn of Africa and presented in the now open access book, Pastoralism and Development in Africa: Dynamic Change at the Margins, and the commentaries by authors ten years on.

For more, dive into our free online course, which was produced at the beginning of the project to introduce students to the ideas underlying the PASTRES work.

Challenging narratives

What are the key elements of this narrative? Our work challenges several assumptions of mainstream policy across a range of areas. This is summarised in this table, taken from the conference presentation.

| Theme | Existing Narrative | New Narrative? |

|---|---|---|

| Mobility | Mobility is unproductive, inefficient and backward. | Flexible mobility is essential for living with and from variability. |

| Land & Environment | Land use needs to be controlled through rangeland management. | Hybrid, flexible systems allow pastoralists to respond to variable environments. |

| Climate | Livestock are bad for the planet. | Extensive, mobile livestock systems can be good for the climate/environment. |

| Diets | Reductions in the consumption of animal-source products are essential. | Livestock are an essential source of protein and nutrients. |

| Markets | Pastoralists reject market-based development. | Pastoralists are highly engaged in local, embedded, networked markets. |

| Conflict | Mobile pastoralists cause conflict. | Long-term neglect of pastoral areas causes conflict. |

| Disasters | Pastoral areas are disaster-prone, resulting in aid dependency. | Local systems of early warning and disaster prevention (high reliability) need support. |

Subsequent blog posts in this series will explore some of these themes in more detail.

Engaging with Policy

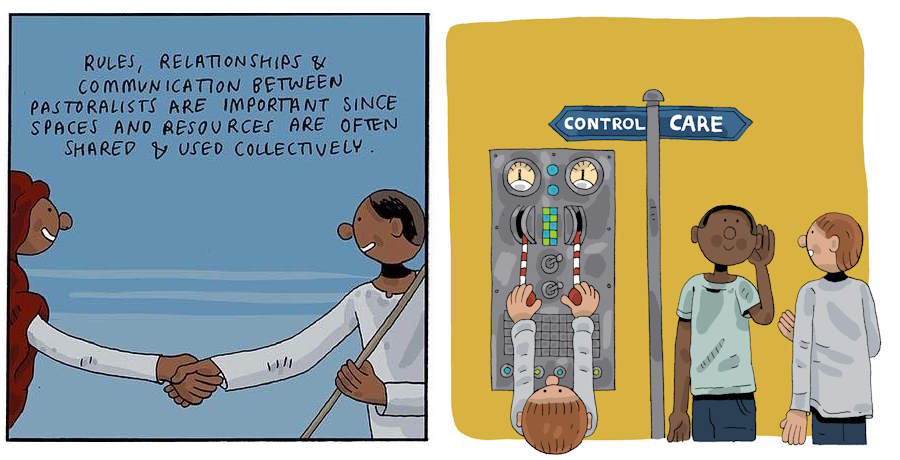

Our Primer on Pastoralism, produced together with the Transnational Institute (TNI) and the World Alliance for Mobile Indigenous Peoples (WAMIP) and available in multiple languages, also provides a good overview of the key themes and arguments, aimed at activists and others engaging with policy change. A paper in the journal Social Anthropology – along with our series of comics on the theme of ‘Uncertain Worlds’– suggests a contrast between a mainstream narrative focused on ‘control’ and a new narrative centred on ‘care’.

These insights build on a long tradition of work on pastoralism at the Institute of Development Studies carried out with many research partners worldwide. In 2019 we celebrated 50 years of this work with the publication of an archive IDS Bulletin and a new introduction written by the PASTRES team, together with Jeremy Swift. A bibliography of work by IDS and partners on pastoralism over many years was also published as part of the celebrations.

The biases of current policy are seen worldwide, as shown in a series of papers on Europe, the West Asia and North Africa, Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Different historical and political contexts of course shape how policies are played out, but basic misconceptions about extensive, mobile livestock systems persist. A paper in the Rangelands Journal summarises these findings, suggesting ways forward. Such misconceptions apply as much to Africa around environmental management debates, as they do in the UK or more broadly across Europe around the reform of the European Common Agricultural Policy.

Old myths about pastoralism have a habit of persisting, but identifying the core principles that are the foundation of successful pastoralism is essential for defining a new narrative.

Dialogues and visual methods

Throughout the PASTRES project, we have engaged with policymakers, field practitioners, activists, and donors from across the world, through various meetings in Europe, Africa, and Asia, as well as presentations to global fora, focusing on food systems, agriculture, climate, uncertainty and so on.

PASTRES contributed to the revisiting of the DANA Declaration 20 years on, as well as actively engaging with the UN Climate Change Conferences of the Parties (COPs), the UN Food Systems Summit (and counter-summit), the International Congress on Extensive Livestock Farming and Climate Change, and various events and workshops at the European University Institute and the Institute of Development Studies, our host institutions. The team was also present at various academic conferences, always sharing research-based, policy-relevant results.

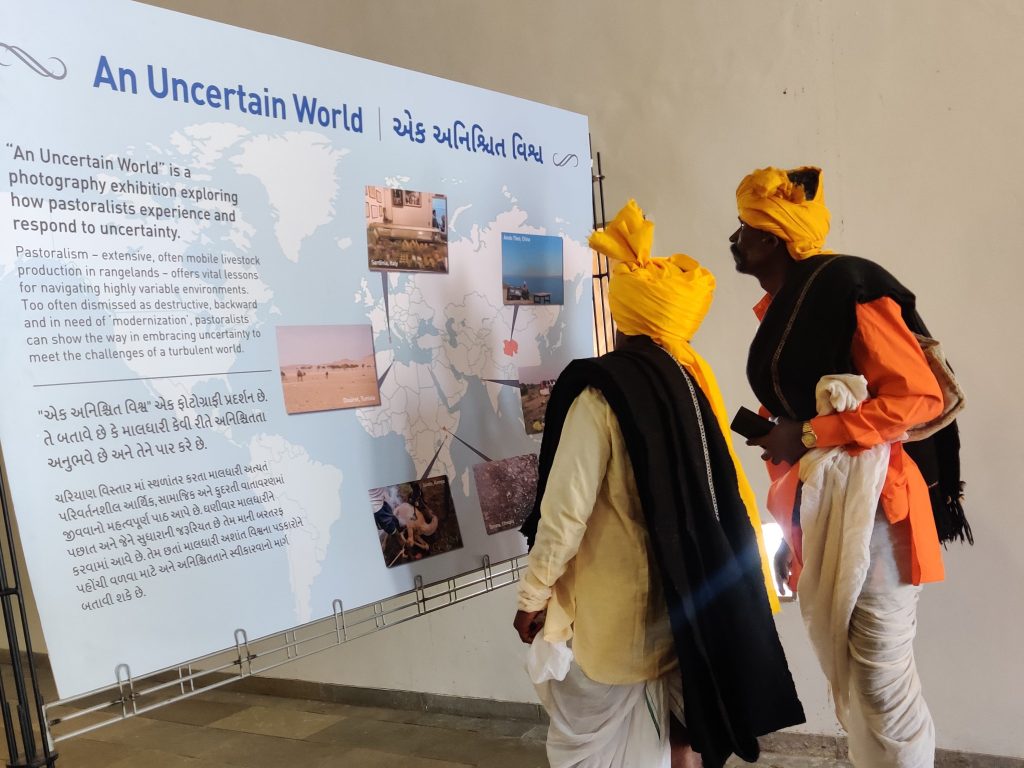

Our work with visual methods – photovoice and documentary photography – allowed the voices of pastoralists to speak through pictures. As Roopa Gogineni and Shibaji Bose explain in a blog introducing the PASTRES Photovoice Guide and documentary photo book, The Rangelands, a decentred approach to using photography in a participatory way can allow diverse perspectives to emerge (see also chapter 2 of our collective book).

Photos also can be shown to policymakers, whether in Brussels or Borana, and PASTRES participated in movie festivals and showcased the work of the team through numerous photo exhibitions across the globe. More generally, arts-based approaches – including the use of traditional crafts – can be used to explore complex perceptions around uncertainty and the future both in policy spaces and within educational settings.

In creating a new narrative about pastoralism – as modern, mobile, productive and an ‘asset to the world’ – some of the assumptions of the past must be challenged. Thinking about pastoralists as ‘reliability professionals’ who are part of a global ‘critical infrastructure’ of pastoralist systems provides a useful way of recasting debates.

Together, our work aligns closely with the United Nations International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists set for 2026 and hopefully contributes to a strong global advocacy for pastoralism, offering a new positive narrative for policy and practice.

Explore our work on Policies

Click on the button to explore the archive of posts on this theme.