by Rebecca Webb, Emma Bernagozzi and Perpetua Kirby

There is a growing recognition of the importance of teaching students about sustainability issues. But given the many uncertainties and unknowns, what kinds of learning approaches are appropriate?

In partnership with a leading school-wide initiative in Brighton and Hove, Our City Our World, the University of Sussex is exploring with schools the value of also engaging their students with the uncertainties of sustainability. This draws on the work of the PASTRES project, with its emphasis on the need to acknowledge what is unknown and unpredictable.

Working with uncertainty is important in a context of the modern global school that places a primacy on the certainty of what is known. The dominant approach suppresses an engagement with uncertainties, and its educational possibilities, including how to respond to the enduring and increasingly complex challenges of the twenty-first century.

This suppression follows from histories of education that only champions the authoritative knowledge of the all-knowing master teacher. More recently, this has been intensified by curricula requirements where students are judged and compared universally by what is straightforwardly measured as either right or wrong, as part of the global market of education.

Amongst the challenges students face are enduring complexities of everyday life, such as negotiating familial and peer relationships. There are also multiple additional contemporary examples. These include navigating the ubiquity and pace of developments in social media and artificial intelligence; huge and widening disparities in access to resources, often in close proximity to those with more; and fostering climate resilience and hope, as well as food security and other local solutions to global vulnerabilities.

Students cannot be taught what to do in any of these situations. Rather, they must be taught to consider the intricacies of any give situation. This involves surfacing multiple feelings, noticing competing agendas, acknowledging that there are rarely simple solutions while, nonetheless, making decisions about to think and how to act.

Where working with uncertainty is unfolding

The University of Sussex’s participative research with teachers and students across different contexts, is being undertaken in both schools and in informal education. It explores how to open up moments where uncertainty is a prerequisite for a variety of activities across different subjects and topics. This means that the answer cannot be known by either teacher or student in advance.

This approach requires a commitment by all those involved to remain open, attentive, and curious to what is encountered and shared, including diverse perspectives from all those involved but equally from different knowledge sources.

The role of the teacher is crucial and complex. Their task is not only to ensure that everyone pays deep attention, but also to require students (at whatever age or stage of education) to respond with what it is they see, think and feel, and to verify what might be claimed. This is demanding work but essential for each person to come to their own informed position.

What working with uncertainty might look like

In 2021 and 2022, Rebecca and Perpetua worked on the theme of sustainability, together with Emma, and her class of children aged 9 and 10, in a school in South East England. This work, funded by the PASTRES project, extended research that Rebecca and Perpetua had previously conducted in West Bengal, India, and lowland coastal Ecuador. This allowed a focus on the intercultural translations of working with uncertainty for students’ everyday worlds.

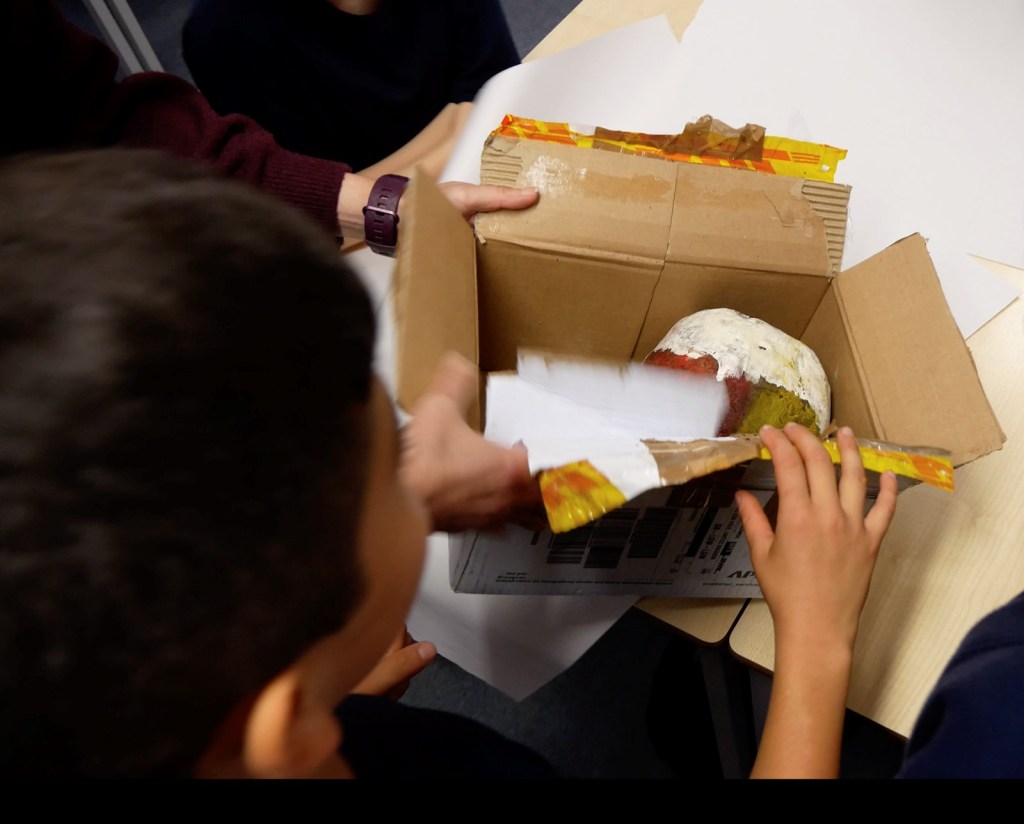

The work began with an exchange of ‘objects that mattered’ to students in all three countries. It included a diverse range of objects, from painted pots made from the seed of the Guayacán salero tree, associated with the critically endangered Great Green Macaw, to chocolate made from local cacao, and a mass of single-use plastics and litter!

Each group was invited to come up with, and deliberate on, philosophical questions in response to the received ‘gifts’. This process evoked open questions and an exploration of students’ own ethical dilemmas. It led Emma’s class to explore, in some depth, the value and complexities of a ‘Fairtrade’ in chocolate.

As a team, we followed up with further opportunities to work with uncertainty in a class project on the topic of water. Emma, Rebecca and Perpetua drew on the PASTRES focus on different dimensions of uncertainty, which includes attending to multiple constructions of knowledge, as well as the material natural world and how this can be experienced, embodied and practised.

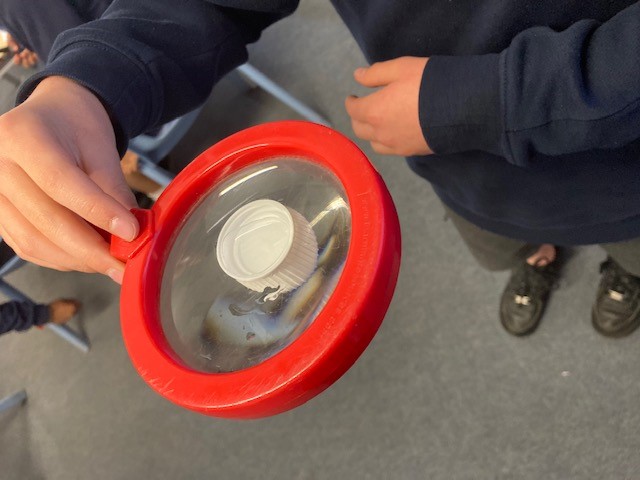

The water project began with the seemingly simple task of asking pairs of students to carry a capful of water to their tables, and to explore it with a straw, a small piece of aluminium foil and a magnifying glass. The children were asked: what do you see? What do you feel? What do you think? What does the water tell you? This absorbed their attention and captured their imaginations. Emma was surprised for how long.

The activity evoked feelings of awe expressed as literary metaphor (the sunlight refracted on the droplet of water on the foil was described as ‘jewelled cloth’); detailed observation (‘It’s like a little magnifying glass if you look through a straw’); as well as curiosities that required further knowledge acquisition (‘I don’t know how it sticks’). After some time of close, playful engagement, did the children begin to reflect on water as a precious resource (‘It makes me think about we shouldn’t waste water’). They were clearly not consumed by asserting a ‘right answer’.

The project continued over five weeks, with different activities demanding close attention, including tasks where there was no one answer. For example, the children had to deliberate whether a Dubai golf course should be awarded an environmental award for the introduction of water preserving technologies: they took on different roles, including those of the golf club owner, a tourist, an environmentalist, as well as the nonhuman: a hare indigenous to the area. (More information on these activities, and many others, can be found in the link at the end of this post.)

A trip to the beach allowed the class to identify different objects and to classify them as either ‘human-made’, ‘nonhuman-made’ or ‘not sure’. The latter category fascinated them. They had most to say about the metal encased in barnacles, painted pebbles, corks and broken ceramics, and weathered wood.

How working with uncertainty might help us live on a damaged planet

These uncertain activities allow children to generate their own curious questions without the diktat of what they should be asking or surmising. None of these activities, on their own, can translate into easily quantifiable outcomes of more active environmental dispositions or actions.

In order to respond to the pressing sustainability challenges in the world, students need multiple educational opportunities to cultivate the ability to attend to, and ‘stay with’, imponderables. This way we might each come to identify what is demanded of us to confront the many uncertainties of living on a damaged planet.

Educational provision that can sit more easily with not knowing the outcomes for any given activity, rather than only ever aiming to suppress uncertainty, opens possibilities for the new and unforeseen. It is this that is necessary to live on and help care for a damaged planet.

Find out more

Read the new online book, Creating with uncertainty: sustainability education resources for a changing world. Accompanying films are also available.