by Ian Scoones

This is the eighth in a series of blog posts that bring together PASTRES work from 2018-2023 around a number of themes. In this post, we discuss the role of moral economies in pastoral systems.

To read through our archive on this theme, click on the link at the end of this post.

PASTRES work has highlighted how standard approaches to social assistance, humanitarian aid, social protection, and insurance are often not well-suited to pastoral areas. Once again, this is because of the prevailing conditions of variability and uncertainty.

Reimagining aid interventions

Standard social assistance and insurance interventions tend to be designed around a simple package targeted often at individuals or households, and responding to a singular event. Delivery assumes stability and fixity, and such systems are often not good at engaging with mobile populations through conventional registration and targeting systems.

The result is that aid interventions often miss their intended mark in pastoral areas. In a paper in Development Policy Review, we make the case that social assistance and humanitarian aid have to be rethought if the uncertainties of pastoral settings are to be taken into account. This means drawing on local knowledge and capacities to identify who needs support and where.

Rather than externally-designed measures appropriate for more stable environments and sedentary settings, a more flexible approach is required, drawing on reliability professionals rooted in communities.

Rethinking insurance

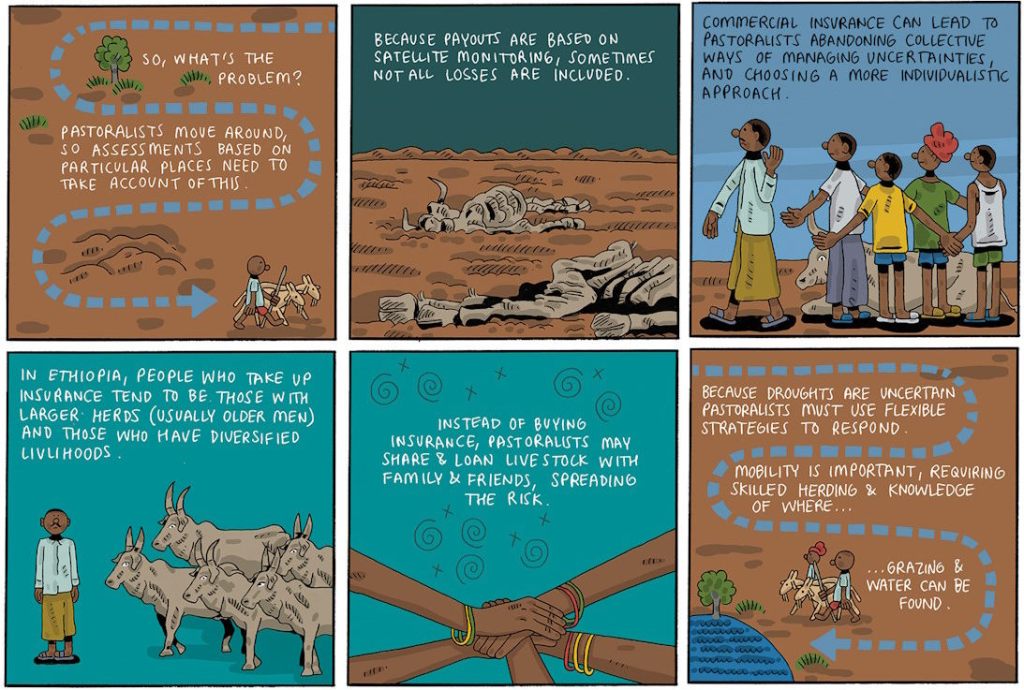

Work by Masresha Taye in southern Ethiopia examined how index-based livestock insurance (IBLI) was being incorporated into pastoralists’ strategies when responding to drought.

The insurance product is being heavily promoted by aid agencies and governments, and is designed to result in payouts when a drought threshold (based on satellite imagery of rangelands) is passed. Payouts are offered to insured people with the aim that the funds are used to protect animals in advance of drought.

The insurance focuses on single hazards (droughts), in delimited areas, and on individuals’ animals, where drought risk is calculated using a particular formula informed by remote sensing data.

By assuming that drought risk can be managed in this way, the design ignores how pastoralists respond to drought, as shown by our paper Uncertainty in the drylands: Rethinking in/formal insurance from pastoral East Africa. PASTRES research found that insurance was bought mostly by richer pastoralists with larger herds, but in no case did it replace local drought response mechanisms.

Such local responses were often more collective, and were focused on diverse hazards, not just one drought ‘event’. Responses very often involved moving animals to new pastures. This means that it is inaccurate to assume that the risk of drought is in a particular delimited space.

Moral economy responses

External interventions – whether social assistance and aid measures or insurance – only ever cover a very small proportion of people around a small subset of challenges.

While important for some, by far the most important response to drought and other combined challenges (such as conflict, disease, market failure, and so on) is always the so-called ‘informal’ responses of pastoralists. These are not ‘informal’ in the sense of not having rules, norms, structures, and agreed processes; rather, they are often simply not seen or appreciated by external agencies and policymakers.

Such responses can broadly be understood as part of a ‘moral economy’: a set of practices rooted in sharing, redistribution, and collective solidarity, and governed by social and cultural approaches. They may be different across social groups (women and men, for example, may have different moral economy practices), between ethnic groups, and over time, as practices change (for example, as state efforts impinge, or different religious influences affect local practices). Whether in the Horn of Africa or Amdo Tibet in China, it is a combination of practices that are assembled in response to uncertainties, which are influenced by diverse institutions.

This was highlighted in our photo documentation and photovoice work. When exploring what ‘uncertainty’ meant to pastoralists across the PASTRES sites and what responses were important, again and again, images that reflected local cultural practices, collective activity, and relationships between people and institutions emerged. Our online exhibition, Seeing Pastoralism and the associated photo book, as well as our guide to photovoice, all emphasise these themes.

As Tahira Mohamed shows for northern Kenya, people come together to help those seen to be in need within the community. This may mean deploying ‘traditional’ approaches to livestock redistribution and sharing if they have lost animals due to droughts, or it may involve more practices facilitated by the mosque or the state. In contrast to the external efforts promoted by aid agencies and others, these are more collective responses, rooted in cultural practices, and involving diverse institutions.

It is these moral economy practices that are at the heart of pastoral survival and response strategies. They are, however, largely ignored by external efforts at ‘aid’ and ‘development’.

Building on relationships and networks

PASTRES work argues that externally-designed approaches need to be rethought to take account of existing practices. At the minimum, this should mean not disrupting or undermining them, but ideally, building on them towards a more collective approach.

This would not be focused on single ‘disaster’ events, but part of a continuous process of support, rooted in relationships and networks at the core of pastoralist societies, suggesting a new ‘politics of anticipation’ for pastoral areas.

Explore our work on moral economies, insurance and social assistance

Click on the button to explore the archive of PASTRES work on this theme.