by Rashmi Singh

Animals such as goats, sheep and yaks have distinct diets and grass preferences. Not only are they aware of the grasses in the pastures, but they also have a deep knowledge of the availability of food and water in the valley across seasons. In fact, our sheep and goats have learnt to reserve grasses for the lean season, such as during the winter months when the entire valley is covered in several feet of snow, and food is scarce. However, recently, with a decrease in snowfall, the grasses are changing, and so are people’s interests. Earlier, animals were stall-fed with a rich mixture of different grasses, but this is no longer the case. People are now more focused on agriculture. Although labourers are hired to care for the livestock, they do not have the rich experience that we have, and they usually tend the flocks in nearby pastures only.

This was the response of an elderly herder who has been rearing livestock for four decades in one of the remotest places in the Indian Western Himalayan region – the Spiti Valley. Even until a few years ago, the valley used to be cut off from the rest of the world for about four months during the winter season. In 2012, during my Master’s internship fieldwork, I was based in Kibber – a Himalayan cold desert and the world’s highest human habitation located at an altitude of 4,200 m AMSL. I was conducting my first on-ground empirical research to document the traditional ecological knowledge of pastoralists, their livestock’s diet and resource use.

From navigating the treacherous mountainous terrain of the Western Trans-Himalaya in the company of yak herders to following the trail of goat and sheep droppings and hoofmarks in the thick temperate forests of the Eastern Himalaya, years of research have allowed me to experience the lived realities and day-to-day challenges of the pastoralists living in the Indian Himalaya. Researchers – both social scientists and ecologists – who work on pastoral systems often experience extreme climatic conditions in some of the most remote landscapes.

Even during the early days of my research on the pastoral systems of the Himalayan region, traces of climate change through warming temperatures were evident, and so was the influence of larger socio-economic changes, improved connectivity, and access to markets and education in the most remote pockets of the Indian Himalaya. I was pleasantly surprised to learn that pastoralists, the masters of adaptation to uncertainty, have used the opportunities of warming temperatures to diversify their livelihood, cultivating cash crops like green peas and apples in the region. With the changing economy, better connectivity, and access to education, there was a transition in the local livestock compositions, local demography, and people started hiring migrant labour for household chores as well as for the herding of their livestock. With the changing aspirations of the new generation and the entry of hired labour, the chain of knowledge transfer was impacted, revealing a clear sign of change in local resource management and herding practices.

Increased depredation of livestock by wild carnivores such as wolves and snow leopards and associated narratives of the conflict between pastoralism and wildlife conservation also surfaced during my early introduction to pastoralism, although I witnessed how pastoralists and wildlife can certainly co-exist. Having learnt about conservation conflicts and state-led pastoralists’ displacements in the name of ‘protecting’ biodiversity in other parts of the Indian Himalayan region, I decided to explore the ground realities of such state-led interventions. These interventions are embedded in the colonial understanding of pastoralism and livestock herding practices, which continue to influence rangeland management policies across the Himalayan region.

In the absence of any regional review on the state of pastoralism and an understanding of the associated stresses and adaptations of the pastoralists across the Himalayan region of South Asia, Dr Carol Kerven and I worked on bringing out a special issue, recently published in the journal Pastoralism: Research, Policy and Practice.

An editorial of the special issue published last week provides an overview of pastoralism in the Himalaya, and the current challenges and adaptations of pastoralists across the Himalayan landscape of Pakistan, India, Bhutan and Nepal.

Pastoralism in the Himalayan Region

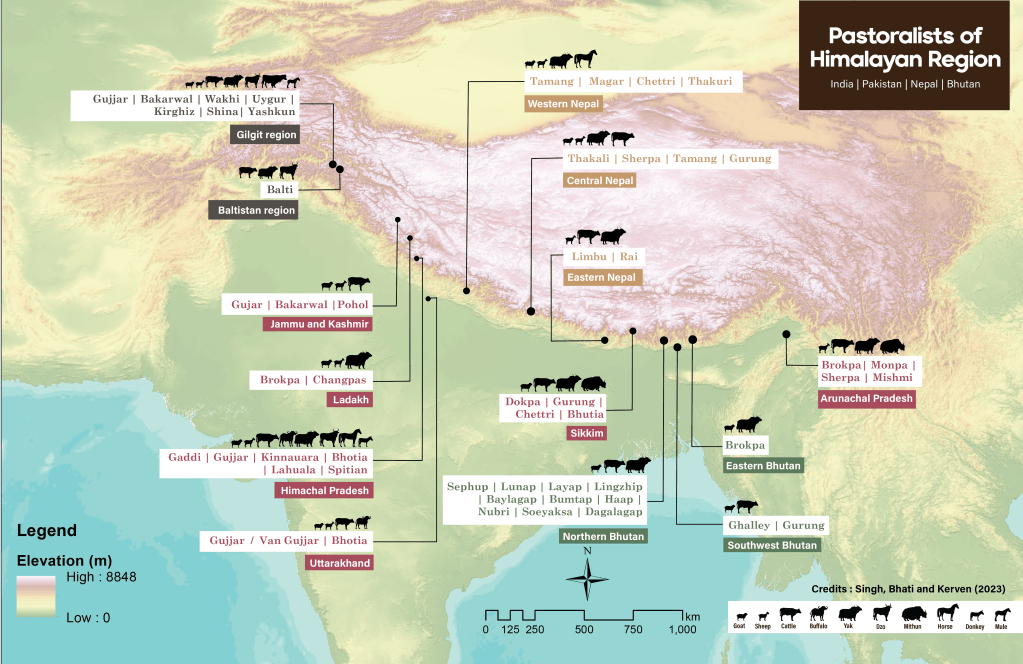

Pastoralists of the Himalayan region across India, Pakistan, Nepal and Bhutan. Credits: Map- Gauri Dangol, ICIMOD, Design- Gurpreet Kaur Sokhi.

The Himalayan mountain range is the youngest in the world and continues to rise at a rate of over one centimetre each year. Along with its religious, spiritual and ecological significance as the water tower of South Asia, the Himalayan region also hosts a great diversity of floral and faunal species that are critical to conservation. Given its remote geography, the region is sparsely populated, and pastoralist communities, including the nomadic, transhumant and agro-pastoralists, are the main inhabitants of the region. These pastoralists have learnt to navigate uncertain climatic conditions but also precarious social and political conditions, often aided by years of experience gained from the support of local institutions and knowledge systems. Making the best use of the climatic variabilities with their seasonal movement across high and low land pastures, the pastoralists maintain a rich assemblage of livestock species composed of goat, sheep, yak, cattle, dzo (a cattle-yak crossbreed), horses and mules.

The special issue focusing on Himalayan pastoralism brings eight case studies from India, Nepal, Bhutan and Pakistan and engages with a wide variety of social and ecological questions. They provide insights into the social and cultural lives of pastoralists of Himalaya, exploring themes about the role of state governance and local institutions, changing knowledge systems, hired labour and absentee herding, human-wildlife conflicts and the newly emerging research domain of disease transmissions between the livestock and wild herbivores in the rangelands of Himalaya.

Changing Aspirations, Knowledge and Labour

With better access to education, newer employment opportunities, and better connectivity, there is an evident decline in the availability of experienced herders among the newer generations. Harsh climatic conditions, the time-consuming nature of herding, and the changes in the family organisation were the key factors associated with shortage of labour. While engagement of younger generations in tourism and other relatively less tedious livelihood options were the primary reasons reported from the study done in Pakistan, in Bhutan, the decline in labour availability was reported as a result of increased yak depredation by wild carnivores and feral dogs.

The pastoral communities, however, responded to the shortage of labour by hiring migrant labourers for herding duties, sometimes through the culturally embedded system, like the Puhal herders of Indian Himalaya. To deal with the decline in the availability of labour, as well as to deal with the declining interest of youth in herding, the authors in the special issue suggested that appropriate schemes are needed to change the youths’ attitude towards grazing practices and make it a lucrative livelihood option.

State Policies and Local Governance

The state has historically played an important role in determining pastoral mobilities and land access across Asia. There have been different motives of the state with regard to pastoral sedentarisation across space and time. The scientific understanding of rangeland functions and the narratives around the role of livestock grazing have moved beyond the linear understanding of the equilibrium rangeland ecological model towards the complex

and more nuanced understanding of rangelands as social-ecological systems. Government policies in the Himalayan region, however, continue to work with the orthodox understanding of fortress conservation and pastoral evictions.

The case studies in the special issue indicate that the rationalisation of state-induced restrictive policies against pastoralists in the Himalayan region continues to occur. Different paradigms of exclusion and their legitimisation are still prevalent, including the perceptions of pastoral societies as backward, livestock grazing as a cause for the degradation of rangelands, and more recent claims about livestock’s contribution to climate change. In the majority of the case studies, the role of local informal pastoral institutions was deemed important to deal with state-induced stress. However, a distinct finding from Eastern Indian Himalaya highlighted how the local informal village institution may create barriers to the smooth transfer of state support to pastoralists.

Climate Change

The case studies in the special issue document climate change as seen through changing timings and duration of rainfall and snowfall and extreme precipitation events such as cloudbursts, floods and landslides. These changes were further perceived to impact the regeneration of grasses, leading to a decline in above-ground biomass. Further, they escalated resource competition between livestock and wild herbivores, increasing the chances of disease transmissions between the two, resulting in intensifying the conservation challenges in the region.

To deal with climatic variabilities and associated extreme events, pastoralists suggested pasture rehabilitation, collective herding, construction of corrals and strategic planning of grassland management. Other than the issues given prominence in this special issue, the role of markets, given the sheer remoteness of the Himalayan landscape, as well as the social security of pastoralists inhabiting the spaces that are strategically important to national security, are some other important concerns to be addressed. These issues can be best addressed by creating an interface between policymakers, practitioners, and pastoralists of Himalaya.

Learn more about Rashmi Singh’s work here.

Thank you very much for this contribution and the hyperlinks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike