by Michele Nori

Pastoralism represents a primary source of livelihood in Sardinia. Traditional pastoral practices which made effective use of local territories have smartly integrated into international policy frames and global market networks.

The Pecorino Romano is today one of the most exported cheeses in the world, and its commercialisation is a primary source of revenue for the Sardinian pastoral economy. The evolving EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has also provided significant economic and organisational support to Sardinian farmers. Supported mainly by these two pillars, Sardinian pastoralists typically navigate and continuously adapt to evolving uncertainties and shifting conditions, even as investigated by a PASTRES case study.

A ‘golden age’ for Sardinian pastoralism

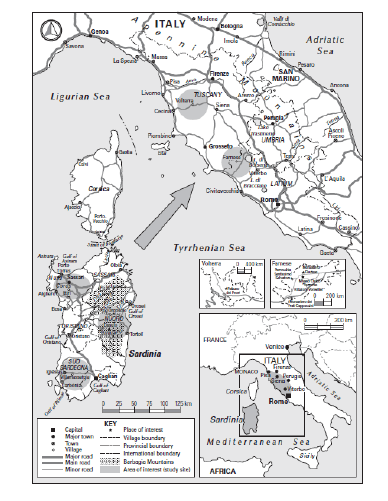

Conditions were particularly good in the middle of the 20th century, when, due to a constellation of factors, Sardinian pastoralism enjoyed a ‘golden age’. Things were so good that lands farmed for cropping in the Campidano and Nurra plains were purchased by mountainous herding households and converted into grazing or animal feed lands. Pressured by growing commercial opportunities and increasing environmental constraints, Sardinian pastoralists undertook ‘long transhumance’ in their thousands, which meant crossing the Tyrrhenian Sea and migrating to the central Italian mainland.

Agrarian reforms and industrial evolutions contributed to a dramatic restructuring of the agrarian world. For instance, in central Italy (Tuscany, Umbria and the Latium regions), many rural areas and villages experienced abandonment, particularly in communities situated in inner settings, presenting various forms of agro-ecological constraints to agricultural intensification (i.e., remote, mountainous, drier areas). This meant that Sardinian herding families could find a place to suit them and colonise the new local agro-ecological and socio-economic territories.

Through a process that combined tradition and innovation, Sardinian pastoralism expanded its territories and networks as a response to the uncertainties generated by the important transformations triggered by market forces and driven by policy and institutional arrangements. Migrant Sardinian shepherds reached Italian mainland rural areas with a specific project, which interfaced pastoral production with a strategic articulation of farming systems and market forces.

During their migration, when searching for land, the migrating families not only brought their labour force with them, but also their core production technology – the Sarda sheep breed – which was loaded onto boats and ferries in the thousands.

The Sardinian form of pastoralism differed from that of the mainland, which was centred around the production of wool and the multi-functionality of sheep breeding. Until the mid-20th century, in central Italy, ewe’s milk had been mostly produced and consumed locally as market outlets, and infrastructure was quite limited. But as milk production became the primary objective, the whole production system reconfigured around the Sarda breed, with the related articulation of land and labour resources. Within the newly imported paradigm, milk productivity emerged as a main entrepreneurial objective, with land use reorganised, household resources relocated, and labour patterns and farming practices adjusted through different evolving ecological, institutional, and market-related dimensions.

Apart from the breed, the size and structure of local flocks were also reshaped, as were the land management and mobility patterns. The Sardinian transhumance pattern was initially replicated on the mainland, taking advantage of the local railway system and road network. While the train connecting Orvieto and Spoleto was initially used to carry the flocks to the summer Apennine pastures, it was eventually replaced by trucks. Transhumance reduced consistently through time as the agro-pastoral land use and production patterns evolving in Sardinia started taking over even in mainland Italy, with animal feed increasingly acquired or produced on the farm.

Networks and cooperation

To manage these processes, Sardinian migrant communities skilfully reconfigured their institutional setting. Capitalising on intense social networks, associative forms and cooperative systems were established. Further, acquiring new lands and farms relied on an effective information system, trust relationships and credit schemes.

The pioneer migrants that first landed in central Italy in the early 1950s started scouting the local countryside in search of land and opportunities. They eventually set up operational networks that assisted the incoming community members, either logistically or financially, helping them through ‘fare spazio’ (making room). In certain areas, for example, the acquisition of bars was instrumental in facilitating the local flows of information and money.

These connections and networks have been strategic for weaving interpersonal relationships, which have transformed into flows of relevant information on the availability of land, farms, finances, and markets. The networks informing and feeding the agro-pastoral economy have eventually evolved and expanded to strengthen pastoralists’ representation vis-á-vis landowners and dairy industrialists. It has also empowered them in political negotiations at regional and national levels, including for the allocation of the EU CAP resources.

Through these enterprises, Sardinian pastoral communities have reinvented themselves by projecting their labour, skills, assets and technologies into new territories and uncertainties to tackle the opportunities and risks of evolving institutional and market domains.

The end of the golden age

Towards the end of the twentieth century, the golden age terminated, and so did the migratory flows. Today, the case of Sardinian pastoralists across Italy is emblematic of the difficulties faced by farmers who participate in global agri-food markets from a subordinate position.

As current economic conditions and social recognition make the pastoral profession less attractive for young people, it is up to the immigrant workforce to support Sardinian pastoralists on both the island and the mainland. Today, immigrants from different Mediterranean countries carry out activities related to sheep management and milking, while also performing collateral tasks such as clearing lands, building fences, collecting timber, farming animal feed, producing cheese, and doing other building or mechanical jobs on the farm.

There are exceptional cases where foreign shepherds have engaged and succeeded in scaling up livestock ownership and farm management. However, in most cases, they remain marginal to the sector’s evolution, and they rarely find opportunities to scale up and upgrade into new livestock entrepreneurs. Now, a key challenge all over Europe and beyond is to integrate migratory flows into contemporary pastoral evolutions.